Her Current Condition

You can tell the condition of a nation by looking at the status of its women.

Jawaharlal Nehru

If we were to judge the condition of our nation by looking at the status of our women, what would we find? Since independence, great strides have been made in the areas of women’s health and literacy. Today, we have female politicians, entrepreneurs, doctors, lawyers, engineers and scientists. Today, many women enjoy far more liberty than did their mothers and grandmothers. Unfortunately, this liberty and equality has not reached the vast majority of Indian women. A brief look at their current condition illustrates this point.

A snapshot of inequalityIlliteracy

Even after defining a literate person to be anyone who can just sign his or her own name or write a simple sentence, according to the last census in 2001, only 54% of our women were literate as opposed to 75% of men.2 This is considered to be a staggering gender gap. Of those women who are considered to be literate, 60% have just a primary school education or less.2

Our country offers “free and compulsory education for girls until the age of fourteen,” and much progress has been made in this area. The difficult issue is keeping girls in school. Sometimes girls are withdrawn from school to fulfil family responsibilities: fetching water, collecting fuel wood and fodder, caring for siblings, cooking and cleaning. Girls tend to perform more chores than boys, so the benefit of keeping a daughter at home is greater. There is also the perception that educating a daughter will not benefit her parents. In addition, parents worry that if a daughter gets too educated it will be more difficult to find a match for her, because her husband will have to be better educated than her. A related concern for parents is that the more educated a man they have to find for their daughter, the higher the dowry expenses. Often girls are not allowed to attend school to protect their honour. Some parents are reluctant to allow their daughters to be taught by male teachers or to attend schools that are not separated by gender. The distance from home to school is also seen as a risk to a girl’s safety.

Child MarriageAlmost half (47%) of our daughters are married before the legal age of 18.3 There are many reasons cited for this: unmarried girls are unsafe; younger girls require less dowry; it is easier to find grooms for younger girls. In some regions, social pressure and old customs require girls to marry early and it is very difficult for any one parent to defy the system. In other areas, the severe shortage of girls is resulting in more and more child marriages.

Today, 40% of the world’s child marriages occur in our country.3

Ill-healthToday, one woman dies in childbirth every five minutes.4 This is a very high number by global standards: one-fifth of all maternal and child deaths during childbirth in the world occur in our country.4 The high incidence of child marriage has a lot to do with this because maternal mortality is five times higher for girls under 15.5 Poor access to health-care is another reason; less than half of all births in the country are supervised by health care professionals.6

Indian women are often the last to eat in their homes and often unlikely to eat well or rest during pregnancy. Almost 60% of pregnant women are anaemic.6 Ill-health during pregnancy is compounded by illiteracy and ignorance, because a large percentage of pregnant women are extremely young teenagers. As a result, they give birth to low-weight babies and tend not to know how to feed them.

Almost half (48%) of our children under age five are stunted, an indicator of chronic malnutrition, and 70% of children under age five are anaemic.6 Malnutrition makes children more prone to illness and stunts their physical and intellectual growth for a lifetime. If this child is a girl, she has the worst of it, because there is gender bias in feeding practices. Infant boys are fed more often and for longer periods of time. Medical attention, even basic preventative care like vaccinations, is often withheld from girls.

The issues of education, child marriage and health are intricately intertwined. For example, just a few years of schooling for the mother has been found to reduce the infant mortality rate by 40%.7

Financial DependenceA vast majority of women work throughout their lives, in fact, many households would not survive without the income they bring in. Unfortunately however, much of a woman’s work is “invisible” because it is not considered important by those around her and not recorded and acknowledged in the national workforce statistics. For example, most of the work women do – the collection of water, fuel and fodder (for which a woman may have to walk miles), cooking, cleaning, taking care of children and the elderly, and unpaid work on family land or in family enterprises – is completely invisible. Because they work at home, even the activities that contribute towards a living are considered part of domestic work. In his book, Development as Freedom, Nobel Laureate Dr Amartya Sen expresses this point very clearly:

Men’s relative dominance connects with a number of factors, including the position of being the “breadwinner” whose economic power commands respect even within the family ...While women work long hours every day at home, since this work does not produce a remuneration it is often ignored in the accounting of the respective contributions of women and men in the family’s joint prosperity.

Dr Amartya Sen

Many women are not allowed to join the workforce because it is perceived to diminish the family’s status in society. When women do work because the family needs the income, they work both in the home and at a job outside the home, and their working hours are, in effect, double. In many homes, men’s work and women’s work is separate and clearly demarcated and men do not do women’s work; it is perceived to be too demeaning.

In most industries, women are paid less than men for doing the same work. For example, the increased use of cheap female labour has become an important strategy for landowners to cut costs in agriculture. Employers say they prefer to use women because they are more industrious, work without breaks, and may be hired at 30% to 50% lower wages than men.8

Despite her tremendous and invaluable contributions, in most homes the woman herself does not have any control over the money she brings into the family; her father or husband controls it entirely. Where she does have control, statistics show that she invests more on the family and less on herself than her male counterpart, who tends to spend a larger proportion of his earnings on himself.

The great tragedy is that, in most families, women do not inherit anything from their parents. They do not own any property in their own names and do not get a share of parental property. Women own less than 1% of all the wealth in India.9

Social ConditioningIn our country, most women are materially, financially and socially dependent on men, and society offers them few alternatives. In most families, a woman is controlled by her father and brothers before marriage and by her husband and in-laws after marriage. She is conditioned from childhood to be docile, obedient and domestic. She is excluded from decision-making in every aspect of her life. Her objective in life is to cater to the comforts of the family – as a dutiful daughter, a loving mother, an obedient daughter-in-law and a faithful, submissive wife. Gender bias restricts her mobility, education and acquisition of skills, ensuring she cannot earn an adequate income or ever become independent. Many women are not able to make the most basic of choices: whether and when to have a child. They are controlled to such an extent that they must take permission before they go to the market, or to visit friends and relatives.

Economic dependence makes women vulnerable to violence. Over 40% of Indian women face physical abuse by their husbands.10 Violence against women in families is often justified as being necessary to “discipline” them and to punish them for dereliction of duty. What’s worse is that women have come to accept this as their lot in life. Studies show that more than half of Indian women consider violence to be a normal part of married life and more than half of Indian women believe wife-beating to be justified in certain circumstances.11

Despite this, women would choose marriage over widowhood because many widows live deeply unhappy lives on the periphery of society. Often blamed for causing the death of their husbands by somehow bringing ill-luck, they are shunned at social functions and forced to live extremely restricted lives where everything they do – from what they wear to what they eat – is controlled.

This is not by any means a comprehensive snapshot of the inequality faced by women. They face many other issues, from AIDS to increased crime against women. In addition, all these issues are exacerbated when the woman is poor, and a large majority of women in our country live in extreme poverty.

Why is this happening? Why do we treat women like this? A step back into traditions, customs and mores reveals the answer.

Son-preferenceIndia is in large part, and has been for a long period of history, a patriarchal society. We have always favoured our sons. Despite all the economic progress we have made, despite all the progressive education we have received, one thing has not changed: we have a deep-rooted tradition of son-preference.

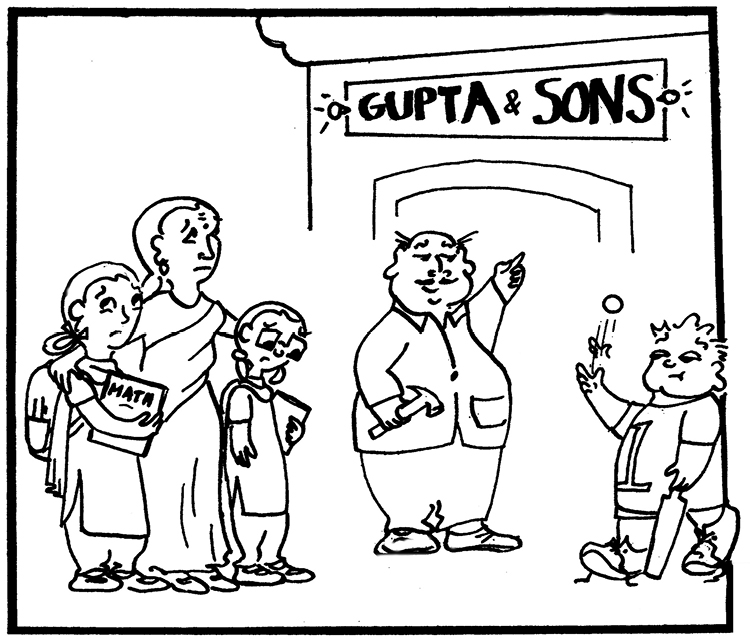

Sons are an assetIn our society, sons are considered to be an asset for many reasons. First, sons continue the family lineage. If a family has only daughters it implies for many people the end of the vansh, the end of the family line. Also, unlike daughters, sons inherit and add to family wealth and property; this is crucial for those who have either property or a business to pass down and want to “keep it within the family.”

It is only a son that makes a father feel like a man and provides a stick in old age. We have so much of land. If I don’t have a son, my brother-in-law’s sons will get the lion’s share.

Landowner in a village12

Due to deep-rooted traditions, it is considered the son’s duty to take care of his parents in their old age; most parents would not consider living with a daughter after she gets married and becomes “part of another family.” There are other advantages to having a son. When parents die, convention dictates it is the son who lights the funeral pyre and performs particular rituals; there are many who believe they will not achieve salvation if they do not have a son to perform their last rites. In addition, there is a perception that sons defend the family and exercise family power; traditionally among the warrior castes, sons were a source of pride and strength, daughters were a source of vulnerability.

The desire for sons is not restricted to men alone. Women want sons too, and not just for the reasons mentioned. In our society, a woman’s status increases when she gives birth to a son, increases further when her son reaches marriageable age and increases even further when she becomes a mother-in-law.

Daughters are a liabilityDaughters are considered to be a liability and often an unbearable burden. Traditionally, daughters are believed to be paraya dhan – another’s wealth. Many parents believe they feed, clothe and educate daughters only to have that “investment” completely taken over by the in-laws, because even if the girl is earning, her parents have no right to that earning. There is an oft-repeated saying that “bringing up a girl is like watering a neighbour’s garden.”

Perhaps the greatest challenge is that daughters are a huge financial burden, especially for the poor and middle classes, because of the crippling expense of marriage and dowry. Besides this, the cultural norms are such that daughters cannot be expected to take care of their parents in their old age. Another mark against them is that daughters have to be brought up with great care and caution due to the increasing lack of safety for women in our society. Daughters also have a lower earning potential compared to sons. And finally, the challenge of raising a daughter does not end after she gets married: very often a daughter is harassed and goes through great suffering at the hands of her husband and in-laws, further exacerbating her parents’ pain and stress.

The combination of all these factors makes the birth of a daughter a painful event rather than a joyful one. The question we must ask ourselves is this: If our social norms dictate that a young girl’s parents are not able to welcome her into the world with joy, what are the chances that society will subsequently allow her a life of dignity and respect?

DowryPrabhuji mein tori binti karoon, paiyan paroon bar bar

Agle janam mohe bitiya na dije, narak dije chahe dar.

O God, I beg of you, I touch your feet time and again,

Next birth, don’t give me a daughter, give me hell instead.

North Indian folk song

Dowry is an Indian tradition that, far from serving any useful purpose, is poisoning our society. One would expect with increased education, economic growth and globalization, that the practice of dowry would die a natural death. Contrary to expectations, the practice has increased substantially in the past few decades. Initially dowry was something the rich indulged in; now it has penetrated deep into the lower income groups, creating a tremendous economic burden on families.

Many families in difficult financial circumstances feel harassed when a girl is born because they know the expense of getting her married and giving her a dowry will be financially crippling. The question of saying no to dowry does not arise. In most cases, refusal to offer a dowry will seal a girl’s fate as a spinster and bring shame upon her family.

There is a dowry death almost every hour in India!

What makes it worse is that dowry is not a one-time financial transaction; demands for dowry can go on for years after the marriage. Religious ceremonies and the birth of children often become occasions for further requests for money, cars or household articles. The inability of the bride’s family to comply with these regular demands often leads to the daughter-in-law being subjected to the threat of divorce, abuse and, very often, severe torture.

More often than not, a girl’s parents know she is being harassed or tortured but do not speak up or provide refuge, because society would ostracize them. In many cases, when the ill-treatment becomes unbearable a young woman will commit suicide to escape from it or to save her parents from further pain and financial ruin. In the worst cases “kitchen accidents” occur: wives are simply killed by the husband’s family to make way for another marriage, which is, in effect, a new financial transaction.

Although dowry has been around for a while, it is India’s recent materialism which has had a direct impact on this newer phenomenon of dowry-related crime. The first dowry death in India was reported in the mid-seventies. Today:

- A dowry-related death is reported once every 65 minutes.13

- Cruelty by husband and relatives is reported once every 7 minutes.13

These numbers are likely to be severe underestimates of the actual scale of dowry-related crime, most of which goes unreported. Most women suffer in silence for many reasons: they have children at home; they are financially dependent on their husbands; shelters are often unbearable choices where hygienic conditions are below par and vulnerable women are further exploited; law enforcement is apathetic; parents are not supportive; and society would blame and shun them if they left their husbands.

A lethal combination: son-preference, dowry and India’s new materialismAlthough son-preference and dowry are old traditions, they are bumping up against the new India – fast-paced, materialistic, acquisitive and technologically savvy – and taking on a new shape. In the new India, modern conveniences and wealthy lifestyles are advertised daily on TV. Those who aspire for this “good life” see dowry as a means to effortlessly escape poverty, increase family wealth, or acquire modern conveniences. Also, in this new India, status is of increasing importance. Given this scenario, sons are crucial: sons earn more; sons can demand dowry and thus bring in even more; sons can inherit and keep family possessions within the family; and sons can go abroad for work, further enhancing the parents’ status. As a result, parents are desperate for sons.

To be the parents of a son is an empowering experience. To be the parents of a daughter can be a shattering experience.

Son-preference and dowry are serious social ills with grave consequences for our daughters. Unfortunately, instead of fighting these social evils we are trying to solve the problem by getting rid of the girl-child. The thinking is: if there is no daughter, there will be no problem.

Sex-selectionThe practice of killing baby girls after they are born, female infanticide, has existed in India for centuries.

“In Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan, the practice of killing new-born girls is part of our history. When a girl was born, the head of the family would place a ball of cotton in one hand and a piece of jaggery in her other hand, and say to her, ‘Pooni katin te gud khayin, veeru nu bhejin, aap na aayin.’ (Spin the cotton and eat the sweet; next time don’t come yourself, send your brother instead). The baby girl was then placed in an earthen pot and the mouth of the pot sealed. The dayi (midwife) was sent to abandon the pot in some deserted place. This was an accepted practice in society; it was viewed neither as a sin nor as an unlawful act.”

Dr Keerti Kesar as related to Vikas Sharma “Waqt Badal Dega Tasveer” Dainik Bhaskar, 22 October, 2009

Contrary to what one might expect, this practice has increased substantially in recent decades.

“... When a male child is born, women bang thalis (metal plates) or fire in the air to announce his birth. But if a girl is born, an elderly woman of the house goes and asks the male members, ‘baraat rakhni hai ya lautani?’ (Do you want to welcome the marriage procession or shall we bid them to return?) If the reply is‘lautani hai’ (to return), everyone leaves and the mother is asked to put tobacco into the girl’s mouth. There is no question of resistance, as it would mean that the mother herself is at risk of either being killed or thrown out of the house.”

Personal communication during fieldwork, 45 Million Daughters Missing 14

With the advent of more advanced technologies, the practice of infanticide has transformed itself into the less overt and far more prevalent practice of female foeticide. Technology now makes it possible to detect the sex of the child in the womb, and many parents, once they find out it is a girl, choose to abort the foetus.

What is the scale of sex-selection in our country?The scale of sex-selection is estimated using an indicator called Sex Ratio: the ratio of females per 1000 males. In most countries women exceed men, because women tend to outlive men: in 2008, Japan had 1053 women to 1000 men and the United States had 1027 women to 1000 men. India’s estimated sex ratio for the same year is very low: 936 women to 1000 men.

Child Sex Ratio, a more accurate indicator of sex-selection and girl-child neglect, is the ratio of girl children per 1000 boy children in the age group of 0 – 6 years. The Child Sex Ratio in the census of 2001 was 927 girls to 1000 boys.

It is estimated that over 50 million women are missing from our population today, and this is largely attributed to the practice of sex-selection. A UNFPA report estimates that in 1991, up to 48 million women were missing from India’s population.

Over 50 million women are missing in India today!

The report hypothesizes that if the sex ratio in Kerala in 1991 had prevailed in the whole country, India would have had 48 million more women.15 If this is an estimate of the number of women missing from the population in 1991, the current number is surely far in excess of that.

One would imagine it must be the most rural, poor and illiterate families who are killing their daughters. However, the opposite is true.

Urban India is doing it more than rural IndiaThe sex ratio is far worse in urban India than in rural India. There are some urban communities with as few as 300 girls per 1000 boys, and it is India’s major metropolises that have some of the poorest sex ratios.

The rich are doing it more than the poorAgain, contrary to expectations, the rich and the middle-class are eliminating daughters at a faster rate than the poor. For the poor, the motivation to abort a daughter is the fear of having to pay dowry at a later date. Affluent families can afford the dowry, but they have either a business or property to pass down, and as a result are obsessed with the idea of having sons.

The literate are doing it more than the illiterateOne might expect that increased education would solve the problem, but educated families are sex-selecting more than illiterate families. Urban, educated and prosperous parents tend to have smaller families, have knowledge of the latest technology, and can more easily afford the expenses of ultrasounds and abortions. As a result, an increasing number of families are using technology to “balance” their families.

The PC & PNDT Act was enacted in 1994, and amended in 2003, making sex-selection an illegal, criminal act in India. But law enforcement has not been effective in stemming the tide of this horrific form of gender discrimination.

More details are provided in the last chapter of the book, “A Final Note,” which includes statistics and information about the scale of sex-selection, the uphill battle against it, and the experiences of women who live through it every day.

The systematic elimination of daughters from our society has reached such crisis proportions that some people have called it a “holocaust” and a “silent genocide.”